Richard Jones isn’t a journalist anymore, but he gets just as obsessed with a lead now as he did when was a young reporter back in the Nineties. “I think it even led to my divorce, to be honest with you,” the 56-year-old, now a tech business owner, tells me over a mocha at a Starbucks in the city of East Cleveland, an oasis of normalcy in a downtrodden area dotted with crumbling mansions and guys doing the junkie lean. A former military man with a solid build, a neat goatee, and a fade, the sugary drink looks incongruous in his hands.

The latest story to get stuck in Jones’ craw? The mysterious murder of Frankie Little, an original member of storied R&B group the O’Jays, who went missing in East Cleveland in the late 1970s. Little wound up as an unidentified bag of bones behind a factory in a small town called Twinsburg years later. He was a John Doe until late 2021, when forensic genealogy revealed his identity. His murder, though, remains unsolved.

Little’s story is a tragedy for more than one reason. He was a musician who stepped off the ride right before it reached its apex, served in Vietnam, and vanished. And although his family missed him, the media and police didn’t seem to care — maybe because he was a rambling man, or maybe because he was Black and it was the Seventies. He received a burst of attention when he was ID’d, but the search for justice has been slow — Twinsburg is a small town, after all, and the police have their hands full with more recent crimes.

Meanwhile, Jones has been consumed with the case, and has a theory: that Little was killed by a serial killer named Samuel Dixon. A Black man who was convicted in 2003 of murdering and sexually abusing four people, Dixon has been largely ignored by the media, a lapse that could have led to Little’s case going truly cold — that is, if Dixon’s guilty of another murder. I traveled to East Cleveland to meet Jones — and exchanged several letters with a largely unknown serial killer — to see if the former journalist’s theory has weight. What I found adds another layer of horror to an already tragic story.

I’D WRITTEN ABOUT FRANKIE LITTLE and the saga around identifying his body for Rolling Stone in 2022, and I’d never forgotten about him and his family. In August of 2025, an email landed in my inbox, subject line: “Frankie Little Killer Found.” I was skeptical. I’m not the only journalist who regularly gets emails from folks claiming to know who the Zodiac Killer is, or promising some tantalizing scoop that winds up being complete fiction. Still, I replied and set up a time to talk to Jones, the email’s author. When I got off the phone, I was convinced the email may not have been bullshit.

Which brings us back to that Starbucks, where Jones is laying out what he knows about Little’s murder — and who he thinks did it. “I looked at this story, and I was like, ‘This is strange, that this man was killed like that,’” he says, glancing down at a a smattering of articles he’s brought in a folder, including my 2022 feature, “The Mysterious Death of an O’Jay.” In that piece, I laid out the puzzle of how Little was killed — his body was found in pieces, so experts suggested he may have died from blunt force trauma or a shotgun blast and was then dismembered. “It had a personal touch to it, really personal — that or a serial killer,” Jones says. That killer being Dixon, he’s convinced, who is currently serving multiple life sentences in a California prison.

To understand how Jones got to Dixon, you have to take a deep-dive into the murky world of East Cleveland politics — a scene just as shambling as its city, a pet project of John D. Rockefeller that he dumped during the Great Depression. The town has had its ups and downs, but, most recently, it’s decidedly down, with a high crime rate, and more than half the children there living in poverty. Eric Brewer — a “bomb-throwing, hell-raising, score-settling yellow journalist,” according to a 2006 story in Cleveland Magazine — sought to change all that in public office.

A Vietnam vet turned muckraking investigator who once headed up the Cleveland chapter of Curtis Sliwa’s Guardian Angels, Brewer has been using his reporting know-how to defeat political opponents for years. When I meet him at the decaying East Cleveland City Council building in September, he’s working as chief of staff for Mayor Lateek Shabazz. The greying 72-year-old, clad in black and a U.S. Navy ballcap, is still fixated on an old rival, though: Otis Mays, who faced off with Brewer in the East Cleveland mayoral election of 2004.

In the runup to that election, Brewer dug into Mays, and detailed his myriad alleged misfeasances in his publication, The Cleveland Challenger. He was running a competitive campaign, Brewer says, “[until] I did some looking into his background and found out about his college transcript.” Brewer claimed that Mays used another man’s credentials to secure a job as a Cleveland substitute teacher. That man? Samuel Dixon — then his roommate, now a convicted serial killer.

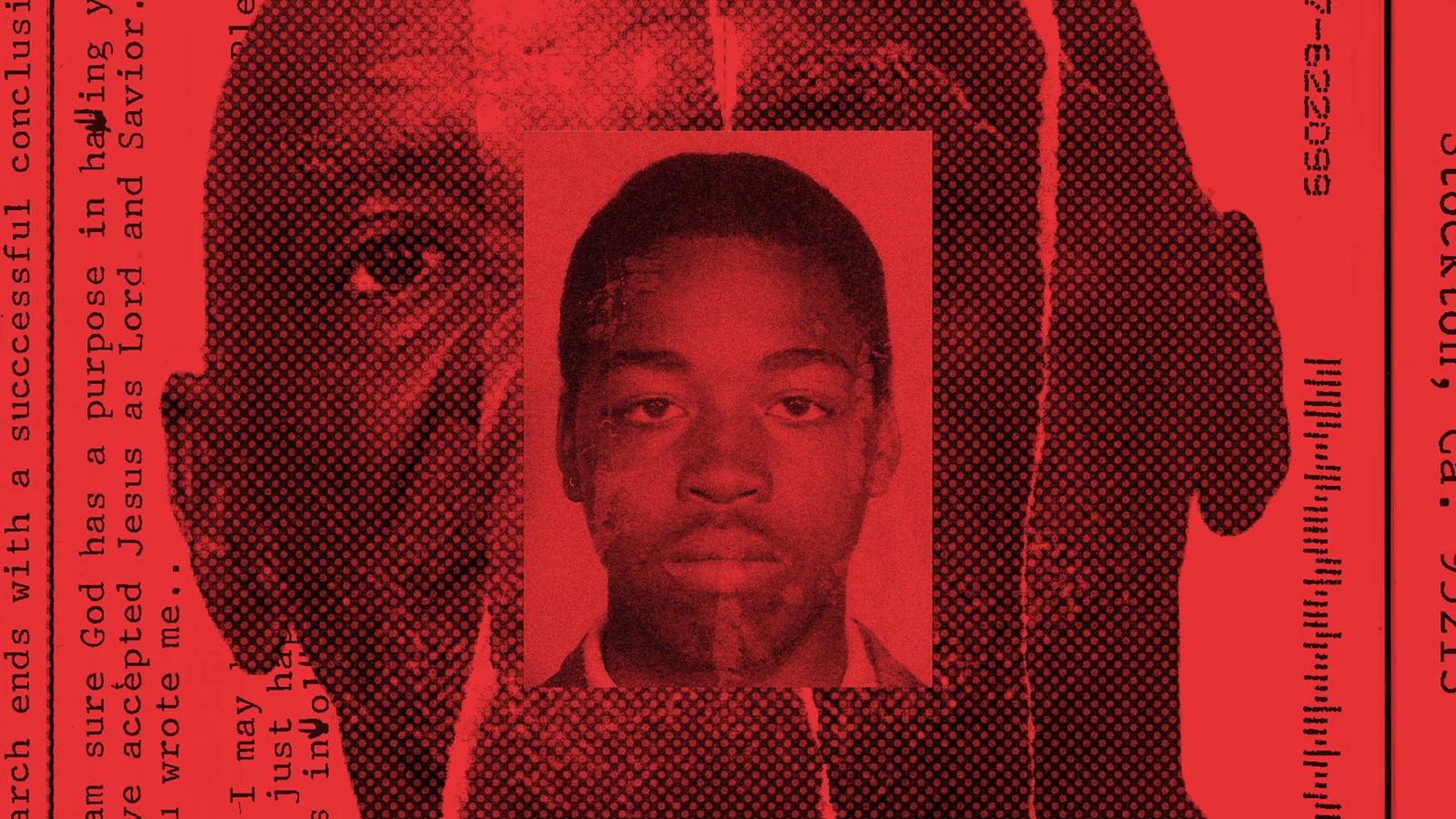

Serial killer Samuel Dixon pictured in 2016.

TWINSBURG POLICE DEPARTMENT

In 2004, The Cleveland Scene said they independently confirmed that Mays used Dixon’s transcript, but, by 2025, the Ohio Department of Education no longer had Mays’ application on file. However, Bluffton College did confirm to me that Dixon attended, while Mays did not. When the Scene asked him about those allegations, he just told them: “I’m gonna reserve that. I don’t want to open any doors, because I still owe some college bills.”

Jones used to write for Brewer at The Cleveland Challenger and Cleveland Life, so he knew Mays well — plus, the 85-year-old never really retired from politics; he still regularly attends council meetings, Brewer says. So Jones was struck when he came across Mays’ name when poking into Little’s death. There was one detail in my story that needled Jones — how, on the last day he was seen alive, Little had sauntered across the street from his house to demand the money he was owed for doing odd jobs for a neighbor. Jones was determined to find out where that neighbor lived and ID him, since the man could have been the last person who saw Little that day.

LITTLE HAD BEEN ON THE UP AND UP back in the Sixties. A lifelong musician who cared more about playing the guitar or sewing his own clothes more than sports or business, he joined the O’Jays in the mid-1960s after they held auditions for new members. His first songwriting credit with the band was for 1964’s “Oh, How You Hurt Me.” “He played a little bit of the Curtis Mayfield style, so we really loved that about him,” O’Jays vocalist Eddie Levert told me back in 2022. “He was a very personal person, you know — Frankie, I just can’t believe that someone would do it like that. He was not the kind of guy that would attract those kinds of people.”

The dream didn’t last long, though. Levert says when the band headed to California in the 1960s, Little was homesick, so he returned to Cleveland.“I don’t think that Frankie could take the struggle,” Levert told me. Local activist and barber Art McKoy recalls giving Little his regular trim at the New York Barbershop, where the musician would drink and bemoan his life choices. “He was a nice young man,” McKoy says. “The group was going good [but] he began to drink and got on drugs, and that’s when the O’Jays left him.” After an Army stint in Vietnam, he fell in love with a woman in California, but left shortly after they had a child, headed back to East Cleveland where he opened a record store and deli with his brother, Johnny.

Little fell in love with a nurse’s assistant and artist named Diana Robinson in the early 1970s and they had a child, Frankie Jr., but Robinson didn’t want to marry him. “He had already been married, and when he left the Army, he never did look his daughter up,” she says by way of explanation. The two of them eventually split, and Frankie Jr. went to live with his father and Frankie Sr.’s girlfriend, Rachella Womack — until his dad vanished in 1979. “I just know at a certain time of night, I was in bed, and I jumped up all of a sudden like something had happened,” Womack previously told me. “That was the night he disappeared and never came back.”

Jones hunted down Womack this past summer and decided to ask her where, exactly, she lived with Little. And as she described the street with the cul de sac at the end, he punched an address into Google Maps and showed it to her. That address, which she confirmed was where the house once stood, was right near Mays’ home — where he’s lived for more than 50 years, some of that time with Dixon, the serial killer.

Later, Jones says, he swung by Mays’ place, a white structure with red trim that was likely grand back in the day, but now looks abandoned, decaying slowly on a street where most buildings have since been torn down. The ex-reporter had a hunch that that had been the house Little visited before he vanished. Mays answered the door. “I think he was kind of out of it,” Jones says, but he says he asked Mays if he ever lived with one Sam Dixon. “He was like, ‘Yeah, he lived here. He lived with me,’” Jones says. As for Little, Mays said he’d never heard of him. “He was lying about that, because the Twinsburg Police had interviewed him [about Little] last year,” Jones adds.

SITTING ACROSS FROM ME AT THE same conference table where I met him three years ago, Detective Eric Hendershott of the Twinsburg Police Department confirms that the cops did interview Mays, although he’s not a person of interest. They just knew he lived close to Little and hoped he might have some info, but he was not forthcoming, the detective says. Hendershott also confirms that Jones called in a tip about Dixon, whom he says the police are looking into in connection to Little’s death. “We started doing a little bit of digging and [Dixon] does have ties to the area,” he says.

It’s in contention that Dixon is a solid lead. After all, Womack initially described the neighbor in question to Hendershott as “an approximately 50-year-old Black male” whom she heard had killed his wife. Still, when I check in with Womack again, she seems unsure how old the man was, actually. She was a teen at the time, so “20 [seemed] old to me,” she says.

Hendershott’s superiors have permitted him to give me a mugshot of Dixon, along with his prison records. The photo shows an old man with a bald head and grizzled grey beard, eyes dark and blank. I joke that I was worried about reading the files before bed back at my hotel — that they would give me nightmares. Hendershott laughs humorlessly. “Yeah, well, I don’t know if that’s bedtime reading,” he says. I see what he means when I get to my room and start paging through the documents. I instantly feel ill.

The child of a minister and a nurse, Dixon was born in North Carolina in 1940. After getting a degree in Bible studies in the Sixties at Bluffton College in Lima, Ohio, he got married — and got into trouble. At 22, he was charged with vehicular manslaughter for a 1962 car crash, as well as burglary and larceny for breaking into his alma mater and local businesses. His defense argued that he had recently undergone a severe personality change. (In later years, he would also be arrested for smuggling two male Mexican teenagers into the U.S. He was not charged. In 1990, he was arrested for soliciting a lewd act.)

After his divorce circa 1965, Dixon moved to Cleveland, where he apparently kept out of trouble, managing local businesses and, according to Mays’ conversation with Jones, living with Mays for a spell. He moved to California in the late Seventies and became an ordained minister in 1989. He also claimed that he’s been HIV positive “since they’ve known about it.”

If the current record is to be believed, Dixon didn’t start killing until he was in his late fifties, an age by which most serial killers have retired. (According to a 2005 journal article, most serial killers are men between 20 and 40.) Dixon’s first three known victims were 37-year-old Robyn Whitehead, 36-year-old Salvadore Reyes, and a homeless woman whose body was never found or ID’d, all in the spring of 2000. He killed 46-year-old Gary Boothe in 2001. According to prison documents, Dixon confessed to the murders in excruciating detail — how he raped their bodies for days after they died and, in some cases, tried to dissolve them with acid. He was inspired, he told a probation officer, by Jeffrey Dahmer, whose childhood home stands less than 20 miles away from the town where Little’s bones were found.

Dixon was initially arrested in May 2001 for possession of Boothe’s rental car, but he claims God told him to confess to the murders while in custody. “You’re going to go down in history,” he told a deputy. “You’re looking at a man who killed four people.” He was wrong about that, though. I only managed to find a few articles about Dixon from the time, and they were low on details.

He wasn’t the only Black serial killer who went largely unnoticed during that era. Dr. Allan Branson, author of The Anonymity of African American Serial Killers: A Continuum of Negative Imagery from Slavery to Prisons, explains that Americans had been so conditioned to see serial killers as white that racism, ingrained or otherwise, prevented many from seeing Black people as being capable of such crimes.

“I remember a friend of mine said to me, ‘We can’t be serial killers. We just started to be quarterbacks,’” he says. “If you look at the social artifacts within our society, all of them point to serial killers as being white males — intelligent white males who are very organized.”

In fact, local police had never heard of Dixon before. If Dixon had, indeed, “gone down in history,” perhaps his name would have come up years ago. “If you say that only certain people of certain cultures are capable of certain things, and then put blinders on, that doesn’t allow you to see the bigger picture,” Branson adds. His research alone has uncovered 163 Black serial killers stretching back to 1919, although he allows that number could be far bigger; “many serial killers in general are never caught,” he says.

“I spoke to Sam over 19 hours about exactly what it was that he did with each one of these victims”

IN MANY WAYS, DIXON’S CRIMES WERE almost as bad as Dahmer’s. Forensic psychologist James Reavis was enlisted by Dixon’s public defender back when he was first arrested to pin down Dixon’s motivations for the killings. “I spoke to Sam over 19 hours about exactly what it was that he did with each one of these victims,” Reavis tells me. “It was early in my career, so I already knew that I would never have another case like this. And 30 years later, I have not. I would take breaks, and I would squat down by my car, and I remember crying on several occasions. I was trying to metabolize what he had told me, there was just not a scintilla of remorse. He was proud of what he had done.”

Dixon told Reavis all about his crimes — how he lured victims home and had sex with them until they said no. Then he drugged them, raped them, killed them, and raped their dead bodies some more. He left bodies in his bathtub and repeated the same process with other victims as he tried to dissolve the corpses with bleach. He left one body to rot in a shopping cart in a park. He didn’t seem much bothered by the murders, telling Reavis of one of his victims: “I was disappointed because [of her] death, I knew then that the sex has to end.”

According to Reavis, a polygraph specialist was equally rattled by these confessions. “He said that he had never been looked at by any human being in the way that Sam [looked at him],” he says. “He took the rest of the day off.”

As for whether Little could have suffered those horrors at Dixon’s hands? That’s still very much an open question. Dixon claimed to his probation officer that he was living in California by 1977, but 50-year-old memories are fallible. Hendershott still hopes to find out whether he could have been still living near Little when Little disappeared — or if he could have returned.

“The detective bureau vetted the lead, and at this time, there is no evidence that ties Dixon directly to Frankie Little,” Hendershott said in an official statement after my visit. “Dixon is believed to have resided on the east side of Cleveland during the 1970s. However, it is suspected that Dixon had moved from the Cleveland area years before Frankie’s murder.… Dixon’s murders also had a sexual motive, and at this time, it is not believed to be a motive in Frankie’s murder.” Still, they haven’t ruled him out entirely. Little’s body was found in pieces in a secluded spot, as though someone had tried to dismember him — much like Dixon’s victims. Right now, the cops are just hoping more folks will get in touch with leads as to who killed Little.

I wrote to Mays, trying to establish what years he lived with Dixon, but got no reply. And when I tried to call him — more than once — he picked up, said nothing, and then hung up when I started talking about Dixon. (Richard Jones, the retired reporter, later told me that Mays was “pissed” at me and was complaining to the folks in the community about my attempts to talk to him. “He just said he didn’t know what you wanted with him and it was BS,” he added.)

And although Reavis tells me he wouldn’t be shocked if Dixon had killed before — especially given the similarities between his victims and how Little’s body was found — he wagers the man would brag about the murder if he’d committed it. “My guess — it is a guess — is that if he had done it and there wasn’t anything obvious for him to lose by admitting it, he would admit it.”

Branson disagrees. “There might have been something in the murder that didn’t quite go right,” he says. “There might be something with regards to Frankie’s personality, or how he was perceived, that this guy didn’t want to be connected with him, or found envious. There’s this whole category of motivations. But, listen, this person died right across the street. Come on.”

Finally, I went to the source itself. I sent a letter to Dixon in prison and asked outright: did he kill Frankie Little and dump his body in Twinsburg? If so, can he please do the right thing and confess? Put Little’s memory to rest? Not long after, I received a typewritten letter on the back of a ripped medical form; the “y” key was apparently broken, and Dixon wrote in the letter where appropriate, making it look like a missive from, well, a serial killer.

“I never knew a Frankie Little, never lived in Twinsburg and he had nothing to do with my case,” he wrote. “Everyone involved in my case has been accounted for. … I am sure God has a purpose in having you write me. I pray you have accepted Jesus as Lord and savior. If not, that might be why you wrote me.” The P.S. reads, “I used [this] paper to save trees.”

Ignoring the concern for my salvation, I was still not convinced. I never asked if he lived in Twinsburg, only if he left a body there. Dixon added that I should feel free to write to him again, so I did, asking, specifically this time, if he lived with a man named Otis Mays in East Cleveland during the 1970s, and if he recalls Mays using his college transcript to get work. Weeks passed, and no more type-written letters appeared on my desk. I wrote to him again, this time offering to send him paper and stamps. Months later, I got a reply, this time handwritten, as his typewriter “quit on me after years of faithful service,” he wrote in barely legible scrawl.

He lived with Mays but doesn’t recall when and how long he stayed, he wrote, before stating — out of the blue — that he didn’t kill one his victims, the homeless Jane Doe. “I was last to see her alive, but I was not responsible for her death,” he wrote — a notable turn of affairs seeing as how he confessed to her murder 20-plus years ago. (One of his letters was written on the back of what appeared to be a request for compassionate release.) He added that he would be happy to speak to me on the phone further, but months passed with no calls, even after I followed up again to make sure he had my number correct. A few more letters arrived, but he didn’t say much of substance — just, “I pray your search will be successful.”

“I’m glad they keep it open so it gives us some relief,” says Little’s cousin. “Hopefully we get some answers”

Nevertheless, the police continue to probe into Dixon’s history — and other possible leads. And Little’s family holds out hope that they’ll someday get closure. When I’m in Cleveland, I swing by Little’s cousin’s house. Margaret O’Sullivan was the key to finding Little back in 2021; one of her children uploaded their DNA to the ancestry site that led to Little’s bones being ID’d. Dressed in light blue cargo pants, a crisp white shirt, and a headcloth, the sprightly 83-year-old perches next to me on the couch while we call Frankie’s brother Johnny on speakerphone.

They’re excited to finally, maybe, close this painful chapter — they’re planning to go visit Frankie’s grave at a nearby military cemetery. “Now, since we know about Frankie, now we don’t have to worry about, ‘Is he coming [home]?’” O’Sullivan says, her voice shaking. “But I’m glad they keep it open so it gives us some relief. Hopefully we get some answers.”

Before I go, O’Sullivan and Johnny ask me if I could help them get in touch with Frankie’s son, Frankie Robinson, who has been in prison since 2006 for manslaughter, a bar fight gone sideways. I’d spoken with Robinson for my last story, but lost touch after his prison changed email programs. I sent him a letter with his family’s phone numbers, and, a few weeks later, we hopped on the phone so I could update him on his father’s case. He’d talked to O’Sullivan and Johnny, and was elated to be back in touch with his relatives. “I got a visiting form — my cousin Margaret wanted to visit,” he says, and I can hear his smile even through the crackly prison phone. “It’s been so long since I had any contact with anybody in my dad’s family. So it’s like a blessing.”

As for Jones? He’s just hoping that him coming forward with the tip about Dixon will help the cops get closer to solving this case once and for all. “I’m a true-crime junkie,” he tells me. “I’m always looking for a story…. Plus, I think the family deserves to know what happened.”