Larry Bird should have been excited about attending Indiana University in the late summer of 1974. The man who had recruited him to come there, Dave Bliss, had been chasing him for more than a year, convinced of Bird’s greatness. Bliss, a young assistant coach at Indiana with blond hair and blue eyes, recorded his thoughts about Bird in his journal again and again. “Guy is going to be really good,” Bliss wrote. “Bird’s better… Bird’s better than all.” Bliss didn’t even care who else the Hoosiers signed that year. “As long as Bird is one!” he noted. And most importantly, Bliss had convinced his boss, Hoosier head coach Bobby Knight, to at least consider the possibility of Larry Bird.

Knight, just 33 years old at the time, had already developed a habit that he would carry with him for the rest of his life: He didn’t like to listen to others, especially not his critics. He had just led Indiana to its first Final Four in two decades in only his second season in Bloomington. He knew what he was doing. But Knight was inclined to listen to Bliss. The two men had been together since the late 1960s, when Knight was the head coach at Army and Bliss was a newly commissioned Private First Class, working on the coaching staff. In a lot of ways, Knight had taught Bliss how to recruit and Bliss had proven himself to be good at it. If Bliss wanted Knight to drive an hour south to French Lick — to watch some kid who most college coaches had never heard of, in a place that most people had never visited, in a tiny gym in one of the poorest counties in the state — Knight would do it. And so, there he was on at least three occasions in the winter and spring of 1974: Bobby Knight was in French Lick to see Larry Bird.

It was a big deal in a small town. At one game that Knight attended at Springs Valley High School in late January 1974, a crowd of some four thousand people tried to pack inside the gym — twice the legal capacity of the building and double the population of French Lick itself. Springs Valley lost that night. In his frustration afterwards, Bird reportedly flipped off opposing fans outside. And the next visit from Knight didn’t go much better. This time, they met inside the home of Bird’s longtime mentor, his former high school coach Jim Jones, on Skyline Drive, on the hill behind the high school, and Knight seemed frustrated that he couldn’t connect with Bird or get him to talk much at all.

“The very best of Knight was there,” recalled Jim Jones’ wife, Joyce. On this evening, Knight was humble, kind, and invested in Bird. Still, it didn’t matter. Bird seemed to be torn between Indiana and Indiana State, a small program that was playing in the hinterlands of Division I basketball, in danger of being banished to Division II, about to fire its head coach, and incapable of filling its new arena in Terre Haute. It made no sense to Knight that Bird would even consider Indiana State, and according to people who were there in Jim Jones’ living room on that visit in 1974, Knight finally expressed this thought out loud. “If you’re thinking about going to Indiana State,” he told Bird, “I don’t know if you can play for me.”

By then, almost everyone in town had an opinion about where Larry Bird should go to college. And in April 1974, with everyone whispering about it, the boy finally made his choice. He walked into Jim Jones’ office at the high school and declared that he wanted what everyone else wanted: He was signing with Knight at Indiana.

In the days to come, Knight drove down one last time for a small signing ceremony in the Valley gym. But it was a seemingly joyless affair. In a photograph that one of Bird’s classmates snapped that day and published in the Springs Valley Herald, neither Bird nor Knight is smiling. They stand next to each other, yet miles apart, as if separated by a yawning chasm that was about to swallow Larry Bird whole.

THIS YEAR MARKS THE 50th anniversary of Bird’s collegiate debut. And because of Bird’s success later — his NBA titles with the Boston Celtics, his MVP awards in the 1980s, his rivalry with Magic Johnson, and his celebrated status as an American icon — it’s easy to forget that he almost didn’t escape French Lick at all. In this alternative reality, we don’t know his name and he never plays basketball. Instead, he gets a job at the Kimball piano plant in French Lick or the cabinet factory over in Jasper, toiling as a wood finisher like his father. And the most tenuous period of Bird’s life came in 1974, at the moment he threw in his lot with Bobby Knight.

In this little window of time, Bird’s parents were divorced and struggling. His mother was working two jobs and his father, a longtime alcoholic who was often unemployed, was careening toward disaster. Lots of people didn’t know how hard life was for Larry, including Knight, Bliss, and everyone else in Bloomington, and Larry was about to make a series of choices that wouldn’t help. It’s these choices that would send Bird tumbling into that chasm, and it all begins in late August 1974 when his uncle drops him off in Bloomington outside his new home, a massive dormitory: McNutt Quad.

MCNUTT HAD A REPUTATION for two things that Bird liked — or would come to like: beer and basketball. Half of Knight’s team lived at McNutt, including every freshman on the Hoosier roster and four players soon to be selected at the top of NBA drafts. That August alone, there were five future NBA players moving into the dorm rooms, 42 years of future NBA service greeting their roommates, and 37,810 future NBA points unpacking their bags. In short, Knight had placed Bird with his people. And they weren’t just clumped together for companionship; they were at McNutt because it was a short walk to the gym, the arena, and a handful of outdoor basketball courts. On a sprawling campus, the players were close to what mattered most to them: basketball. And when they weren’t playing, there were plenty of activities at McNutt to keep them occupied — namely, parties. The McNutt kids were known for throwing ragers, complete with kegs, eight varieties of alcohol, and women.

It should have been a good fit for Bird; he even knew people on campus, people from back home. His high school girlfriend — a cheerleader named Janet Condra, with long hair, fair skin, and a warm smile — lived in the dormitory next door, a five-minute walk away. This could have worked.

Indiana head coach Bobby Knight with his 1973 team, which went to the Final Four. The following year, he recruited Bird to come play for the Hoosiers.

Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty Images

But Bird was troubled in Bloomington from the start. McNutt housed some 700 kids — about one-third of the population of French Lick — and Bird found the campus outside the dormitory walls bewildering. At any given moment that August, 30,000 students were eating in the dining halls, drinking beers on Fraternity Row, trying out for the tennis team, attending the president’s welcome picnic, or piling into cars to go to the drive-in movie theater off campus. This wasn’t a college. “It was more like a whole country,” Bird said later. And he felt like a foreigner in this place. He didn’t even fit in with his roommate, Jim Wisman.

The two young men ended up there together for the simplest of reasons: They were the last two basketball recruits in need of a roommate, and they didn’t seem all that different, at least from afar. Wisman was the son of a postal carrier in Quincy, Illinois, a small city on the banks of the Mississippi River. He was white, like Bird; Midwestern, like Bird; small-town, like Bird. And if it didn’t work out between Wisman and Bird, there were other basketball players for them to befriend at McNutt. They could hang with the two other freshmen on the team, who were living down in room 386, roll with upperclassmen Quinn Buckner and Scott May, or find future NBA No. 1 draft pick Kent Benson somewhere in the same dorm. It would be fine.

But the room assignment, random as it was, revealed something important about the operation at Indiana: Bliss had recruited Bird and Knight had signed him. But Knight had failed to get to know Bird at all. And it didn’t take long for people to realize that pairing Wisman with Bird was a mistake. Wisman was polite and articulate — a good kid, but also different. “He was,” Bliss realized too late, “maybe the antithesis of Larry.” Bird had one bag of clothes while Wisman had arrived on campus that August with a full wardrobe. On the day they moved in, Bird watched Wisman unpack, thinking, “Man, I don’t have nothing.” Teammates who visited their room that August left with the same feeling. John Laskowski, a senior guard, remembers going there to welcome the two freshmen and seeing three things in their room that he would not forget: Wisman’s full closet, Bird’s empty one, and the wide gulf that seemed to exist between two new roommates. “It was just kind of two different worlds,” Laskowski said. Even Wisman’s generosity didn’t help. At some point, he told Bird he could borrow his clothes, and he even loaned Bird money when Bird’s cash ran out. But Wisman was almost seven inches shorter than Bird; most things in that closet weren’t going to fit him. And by early September, Bird began asking himself a question: “How can I keep wearing Jim Wisman’s clothes and accepting Jim Wisman’s money?”

In dark times like these, Bird had typically sought solace in one place — the basketball court. But Bird couldn’t find any peace at Indiana. In pickup games in the Hoosiers’ arena, Assembly Hall, his new teammates treated him poorly, Bird thought. He complained later than Kent Benson — the Hoosiers’ 6-foot-11 center, a future two-time all-American — took his ball. Sometimes, in the schoolyard picks before scrimmages, Bird wasn’t selected at all. Then, in early September, he injured his toe while playing on the outdoor courts. In addition to everything, Bird was now hobbled, limping off to class on an enormous campus that was 15 times bigger than French Lick.

It all started piling up inside of him until he began to consider a plan: Maybe he’d go home. Maybe he’d leave.

Bird said later that he told no one about his intentions. Said he kept his doubts and his darkness to himself. But folks on campus that September saw through him. And at least one person sensed Bird’s frustration during the final pickup game that Bird played that month. The guys were in the locker room after a scrimmage. People were showering and Bird was angry, recalled team manager Larry Sherfick, because he wasn’t playing or because people weren’t passing him the ball.

As Bird stewed over these slights, Sherfick said, one of the players in the locker room made a comment loud enough for everyone to hear: “Tell us again, Larry — where are you from?” The implication, Sherfick said, was clear. Bird was a nobody from nowhere. And at this point, Sherfick recalled, Bird turned to him for help. “He looks at me,” Sherfick said. “He’s pointing at me, and he says, ‘He knows where I’m from. Tell him where I’m from.’”

It was getting late by then and Sherfick was annoyed by the shenanigans. “Frankly, I don’t want to get into this,” Sherfick recalled thinking. “I’m just trying to get my job done and get back before the dinner line.” So, he stayed out of it. He said nothing. He didn’t come to Bird’s defense — a choice he’s thought about from time to time over the years. “I’ve felt some remorse that I didn’t stick up for him,” Sherfick said, especially after he heard about what happened next. On the second Friday of September 1974, about three weeks after Bird arrived in Bloomington, Bird walked into Bliss’s office, Bliss recalled, and announced that he was leaving.

Outside, it was starting to feel like autumn. Cool weather was moving in and kids on campus had big plans for the weekend. The Hoosiers were playing the Illinois Fighting Illini the next day in their first football game of the season, and students at Willkie Quad, a dorm about a mile from McNutt, were planning a big party. But Bird wasn’t going to be there. Bliss could tell he was serious about leaving, and there was nothing Bliss could do to stop him. Knight was out of town that Friday. He was making an appearance at a coaching clinic at a Marriott Hotel up in Fort Wayne. People were putting down $25 at the door to meet the great coach of the Indiana Hoosiers, to hear him talk about basketball, and to laugh at his inappropriate jokes, and by the time Bliss reached Knight by phone sometime later, Bird was long gone.

He had packed his things, walked out to Highway 37, and hitchhiked home. A trucker got him as far as Mitchell, and Bird figured out the rest from there.

LARRY’S MOTHER, GEORGIA, was furious when she learned that her son was back in French Lick. His father, Joey, took a different view of things. According to Larry’s recollection, Joey supported Larry’s decision to leave Bloomington. “Don’t look back,” the father informed the son.

But in the fall of 1974, Joey Bird wasn’t in the best position to be giving advice. He had been making poor decisions for at least 30 years. He never finished eighth grade; left a good job to enlist in the military in 1944 when he was still just 17; went AWOL and got caught drinking liquor on his ship before even shipping off to World War II; re-enlisted to go to Korea; spent a miserable winter there, fighting the Communists; came home scarred by what he had seen in those frozen foxholes; took to drinking; became a presence in the local bars around French Lick; couldn’t seem to hold down a job; and now seemed to be descending into darkness. Around the time that Larry returned home, his father was talking about ending his life, ending it all.

Against this backdrop, the son made a curious choice of his own. Larry enrolled at a small technical school in West Baden Springs, just north of French Lick, and joined the basketball team there. He had left Indiana University — one of the best basketball schools in the country, run by one of the most successful coaches in America — to play for Northwood Institute.

Northwood was exactly as small as it sounded. It had a total enrollment of about 250 students and a strange and singular campus. Northwood’s dorm rooms, classrooms, and offices all existed inside an old domed hotel that had seen better days. The grounds outside were overrun with weeds and the upper floors of the hotel were completely vacant. There weren’t enough students enrolled at Northwood Institute to fill them. For all of these reasons, members of the Northwood team were shocked when their head coach informed them that Larry Bird was joining the roster. Glen Tow, a five-foot-five guard, almost felt bad for Bird, and his teammates felt the same. They had enrolled at Northwood because they didn’t have an option to play elsewhere. The team’s center, Dave Earley, might have been working in the timber business with his father over in Seymour if he hadn’t come to Northwood. One of the team’s forwards, Kent Hutchinson, might have enrolled at a little school in Franklin, Indiana, if a Northwood coach hadn’t reached out to him. In fact, basketball wasn’t even the primary sport for many of the guys on the team. They were there to run track or play baseball. And now they were sitting in the windows of their rooms upstairs, watching Larry Bird walk across the atrium of the old domed hotel and wondering what he was doing there.

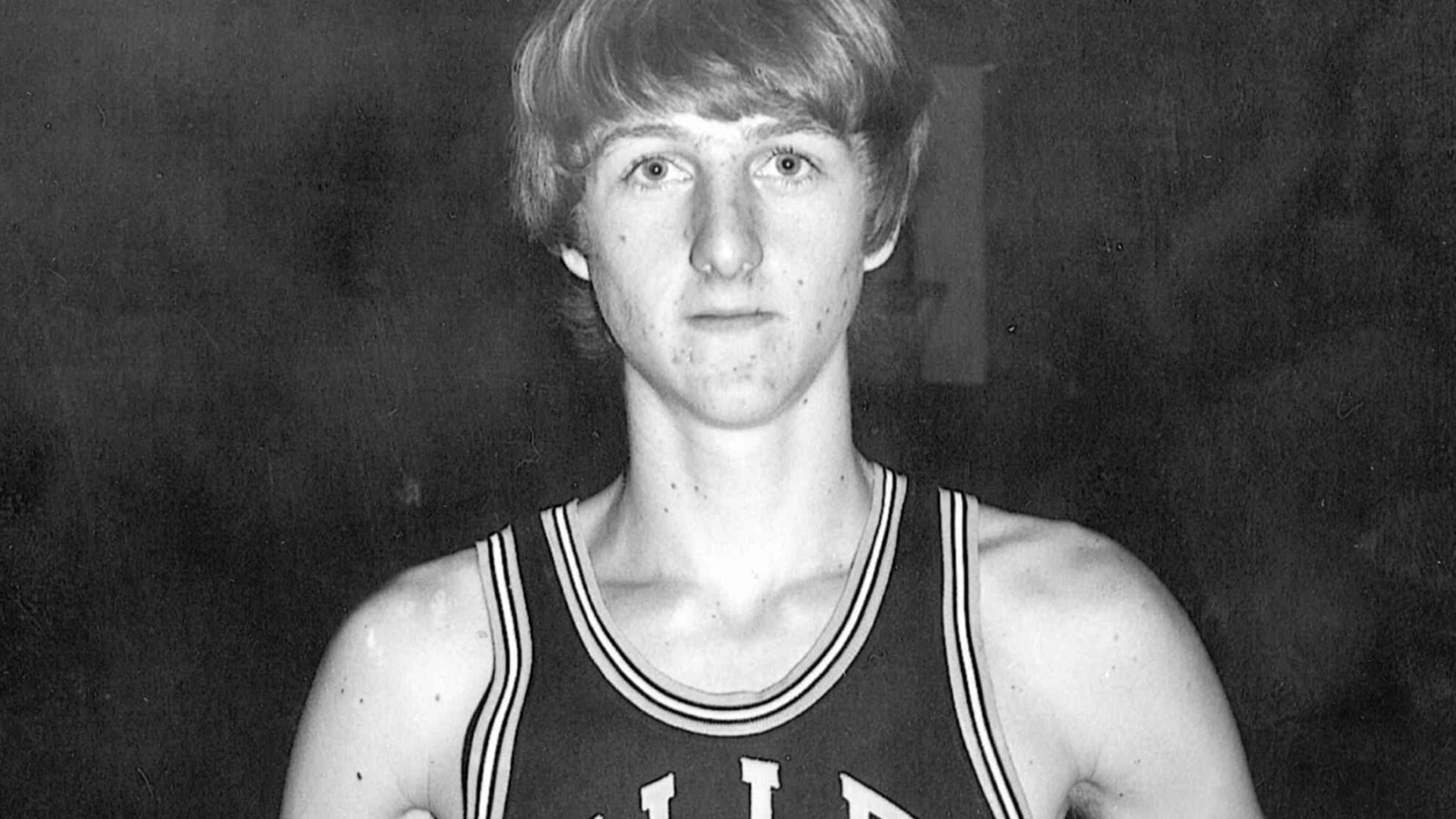

Bird as a high schooler. He had trouble adjusting from his tiny hometown of French Lick, Indiana, to IU, where the student body numbered around 30,000.

Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame

Bird seemed to be asking himself the same question. At one point shortly after he showed up, Northwood’s head coach asked Tow to help Bird get the books he’d need for class. “So I got the list and everything and took the list to Larry,” Tow recalled, “and Larry just looked at me and said, ‘I’m not going to need these books.’” Tow wasn’t sure what to make of the comment; he and all the other guys were hoping to get a degree. But for all the doubts they might have had about Bird’s academic commitment, no one had questions about his work ethic in the basketball practices held that fall in a little gymnasium across the road.

The gym, called Sprudel Hall, was the last remaining relic of long-defunct West Baden High School, and it too was showing its age. At places on the floor, the ball wouldn’t bounce at all. Bird’s new teammates couldn’t wait for practices to be over. Northwood’s culinary students were always churning out great food — lasagna, chicken cordon bleu, and Cornish hens served in warm nests of baked bread — and no one wanted to miss the meals. But Bird didn’t care. While everyone left for dinner, he’d stay at Sprudel Hall, shooting and shooting. Sometimes, Dave Earley, the team’s best player, would drive by hours later and find the lights still on and Bird still inside, playing games against himself. He’d bounce the ball off the bleachers, retrieve the off-kilter carom, and throw up off-balance shots from 35 feet out. Or he’d drop-kick the ball off the wall, chase it down, and shoot from wherever he scooped it up again. It didn’t matter if he was 10 feet from the basket or 50, Earley recalled. Bird would just turn and shoot, preparing himself for some future moment in some future game.

The Northwood guys had never seen anything like it, and Earley began to wonder: Who is this Larry Bird? He’d heard stories that Bird’s father drank too much and couldn’t hold down a job, and because there was nothing to do in town, Earley and a couple of other guys went out one night that fall to investigate the situation for themselves. They piled into Earley’s 1968 Oldsmobile, followed the railroad tracks behind the high school, found Georgia Bird’s house in the dark, and idled in front of it on the street.

They probably weren’t there for more than 10 seconds, but Earley would never forget the silence that filled the car — “dead silence,” he said — as everyone eyed Bird’s house. It was small, crooked in places, and not just poor. It sort of felt sad, Earley said, and he realized in that moment why Bird stayed in the gym and never seemed to go home.

“There wasn’t really anything to go home to.”

SOMETIME THAT NOVEMBER, just before Northwood’s first game and a couple of weeks before Bird’s 18th birthday, Bird stopped coming to practice. He quit the team and dropped out of school again — developments that surprised no one at Northwood. Tow had wondered from the start if Bird would stay, and the next time Tow saw him, Bird wasn’t playing basketball at all. He was working for the city, riding on a garbage truck and collecting trash.

Tow didn’t say anything to Bird that day; he might have just waved, he thought later, as the garbage truck rolled by. He certainly didn’t say what he was thinking: that Bird was wasting his talents, that Bird was wasting his life. It disappointed Tow, and it disappointed lots of other people, too. They’d see Bird that winter shoveling snow, fixing streets, or picking up the trash and wonder why.

But Bird liked working for the city. The job put money in his pockets and helped him buy his first car, a used Chevy. It also gave him something to do while his father unraveled even more. That December, in the county courthouse, Georgia Bird asked the court to hold Larry’s father in contempt — for failure to pay child support — and according to Larry, his father went dark. By Christmas, Larry was worried about him, and by the first week of February 1975, the police were looking for him, knocking on the door of Joey Bird’s parents’ house in West Baden.

It was a Monday, right in the middle of the Springs Valley basketball season, and folks in town had moved on by then. No one was talking about last year’s high school team. No one was talking about Larry Bird. The boy had made his choices and the father was about to make his choice, too. When the police came calling, Joey Bird grabbed a shotgun, turned the barrel around on himself, placed it against his head, and pulled the trigger.

In an instant, he was dead. By the end of that week, Larry was at his father’s funeral, the family gathering on a hill in Dubois County, south of town, and by the end of the month, Larry had bottomed out entirely. He wasn’t playing basketball at Indiana anymore and he wasn’t even playing for the likes of Northwood Institute. He was playing in a men’s league — glorified pickup basketball — with a collection of workaday guys who had mortgages, wives, day jobs, and children. One of the greatest basketball players of all time was about to pull off a feat that’s hard to imagine. Larry Bird was about to disappear.

Excerpted from the book HEARTLAND: A Forgotten Place, an Impossible Dream, and the Miracle of Larry Bird, by Keith O’Brien, out March 3. Copyright © by Keith O’Brien. From Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Publishers. Reprinted with permission.